The concepts behind Facebook’s rumored “WANT” button are rooted in the idea of the “intention economy” and are generalizable beyond the Facebook ecosystem. Both customers and enterprises, using today’s existing infrastructure and conventions, can create and listen for intention signals using open, lightweight mechanisms, with customers creating those signals and enterprises listening for them. The approach described here outlines one such mechanism.

The Facebook “WANT” button is the canary in the coal mine for the “intention economy”

On June 27, 2012, blogger Tom Waddington discovered that Facebook had included the ability to create a “WANT” button in its software development kit (SDK). According to reports from Waddington, as well as others including Inside Facebook, Gizmodo, VentureBeat and Mashable, the button will be a way for individuals to indicate their desire to purchase a product.

Inside Facebook had the following to say:

“Just as the Like button allowed Facebook to collect massive amounts of data about users’ interests, the Want button could be a key way for the social network to collect desire-based data. A Want button plugin will make it easy for e-commerce and other sites to implement this type of Facebook functionality without having to build their own apps.”

The fact that Facebook may be testing the “WANT” button is the clearest indication to date that we are on the path to the “intention economy.” Doc Searls has described the intention economy as “an economy driven by consumer intent, where vendors must respond to the actual intentions of customers.” Others, such as John Hagel, have stated that this thinking around the intention economy “is a graphic demonstration of the shift from push to pull that is disrupting our business world.”

The “WANT” button, however, is hobbled by the fact that it only works in the Facebook ecosystem and, more importantly, appears as if it’s going to require a non-trivial bit of work to implement. Additionally, the “WANT” button is 100% driven by vendors who are selling items – if the vendor hasn’t indicated through a bit of arcane code that the “WANT” button is available for an item, the button will not appear. There is no way for an individual to initiate the conversation around desire for an arbitrary product or service.

Although definitely a step in the right direction, indicating interest through the proprietary “WANT” button within Facebook is a relatively coarse-grained way for a customer to signal intent.

Internet culture has already created conventions for signaling

That said, there are other pieces of the intention puzzle already in place that can be used. The expression of intention is, at its core, a signal. For the past few decades in particular, however, most of the “signaling” between vendors and customers has come from the vendor in the form of advertising, PR and the like. (In fact, one could argue that the whole discipline around creating “messaging platforms” for large enterprises is, at its core, an attempt to create clear, differentiated signals from the vendor side.) However, as more customer-driven publishing and communication methods have been created, first with blogs and more recently with customer-created conventions on top of proprietary platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and Pinterest, individuals have started to introduce their own signaling mechanisms into the fray. Here are two examples:

The hashtag (#) is a signal of topic, organization or keyword. For instance, including a hashtag of #bacon in a post or tweet makes it easy to search for posts that are about bacon.

In the example above, the #bacon hashtag makes it easy to find this post.

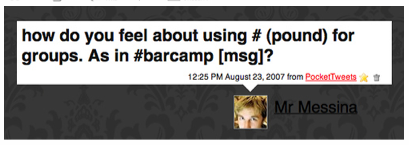

The interesting thing about the hashtag construct is that is was created organically. It wasn’t created by a committee, it wasn’t designed by an organization, it wasn’t created as part of a marketing campaign. The hashtag was simply proposed by Chris Messina (@chrismessina) in a single tweet in 2007 as a way to easily find related conversations about BarCamp that were happening online at that time.

You can learn more about the history of the hashtag here.

Since then, the humble hashtag has become the de facto signal that the text that follows it is related to a topic or is a concept of importance to the author of that post. In contrast to the “WANT” button, which needs to be supported by Facebook and explicitly supported by the vendors of products or services that a customer might “want,” it’s important to note that there is no central organization that creates or approves hashtags. Hashtags follow the “NEA” protocol of the open internet:

- Nobody owns them

- Everybody can use them, and

- Anybody can improve them

The NEA concept is important. If something conforms to NEA, it can scale, grow, evolve and morph as a market evolves, without constraint. This enables the possibility of a very fast, very efficient process of innovation and improvement.

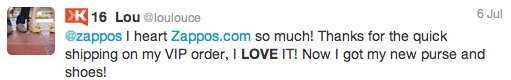

If the hashtag is a signal of topic and organization, then the at-reply (@reply) is the de facto signal of social connection. The at-reply convention has evolved to signal that the message contains information that is of particular interest to a particular individual or entity.

Lou really, really loves Zappos and wants to make sure that Zappos knows it.

Like the hashtag, the concept of an “at-reply” evolved organically, though a conversation of individuals on Twitter. You can learn more about the history of the at-reply here.

Sometimes these conventions get combined. For example, Micah Baldwin (@micah) proposed the concept of a “Follow Friday” online event, when he sent a tweet and named a number of individuals with the at-reply notation. In doing so, he started a ritual that many people invoke every week on Friday. Now, every week tens or hundreds of thousands of people recommend others in their networks as individuals who are worthwhile to follow on the Twitter service using the #followfriday and #ff hashtags coupled with those individuals’ Twitter handles.

Although both the hashtag and at-reply conventions were initially invoked on Twitter, they are concepts that are platform agnostic at their core. Since then, both concepts have jumped to other platforms including Facebook, Pinterest, Instagram and Google+, underlining the fact that useful, simple solutions to individuals’ needs are not constrained to any one technology silo.

A question of intent

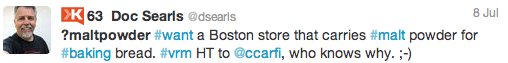

In the same way that the hashtag is a signal of organization and the at-reply is a signal of connection, the question mark (?) could be a signal of intent. For example, including ?rentalcar in a post could indicate that the poster has intent to procure a rental car, the inclusion of ?flight could indicate that the poster is looking for airfares for an upcoming trip, and so forth.

The first example of this I’ve seen in the wild occurred earlier this week.

For vendors, this approach triggers a number of things, the first of which is that it turns on a lead-generation mechanism with extremely high fidelity. If an individual has explicitly stated intent via this mechanism, that individual is the hottest possible prospect. This mechanism is beacon to vendors: “Here is a customer who wants to buy what you’re selling.”

Organizations are already using tools such as Radian6, Sysomos, Attensity, and even free tools such as Tweetdeck and basic Twitter search to seek out individuals who are mentioning their brands. The extension of those listening efforts to additionally listen for intent signals of this type are nominal. (Listening tools like NeedTagger are already starting to move in this direction.) From the customer’s side, there is a similarly minimal learning curve required. Anyone can state intent in this manner using existing tools in a matter of moments.

We saw that explicit technical support for concepts such as the hashtag and at-reply did, after a period of time, eventually become a part of the systems upon which they were built. It is a similarly straightforward effort for platforms such as Twitter, Facebook and Pinterest to support this question mark based notation for intent. In doing so, those platforms would be also able to generate highly valuable trend information on the types of intention signals that are “trending” across various geographies and demographics, in the same way that Twitter and Google+ today highlight trending topics within their services based on the frequency of use of particular hashtags.

A statement of permission

There’s a flip side to this idea of unambiguously indicating intent with a statement such as ?flight. By explicitly indicating intent, an individual is indicating interest and is also explicitly giving permission for vendors to contact them. This is the grail for marketers. In the current state of affairs, there is still a huge differential between what vendors, advertisers and publishers of information believe that a particular individual is interested in, and the actual reality of the situation. We’ve all received “targeted” ads on social platforms that are so off the mark to be laughable. With clear intention signals, however, that guesswork is reduced to near-zero; the interaction is all signal and no noise. (Huge kudos to @lisastone for this insight on how the flip side of intention is permission.)

So…what do folks think about using the ? as an indicator of intent, in the same way that we’ve used other signaling mechanisms as noted above?

Excellent post! I really like the proposal for an NEA version of the “Want” button.

I think the expression of intent might be most powerful if coupled with the idea of a “Fourth Party.” To be more specific, if I say “?RentalCar Friday to Monday SFO,” I really don’t want to be engaged in twelve conversations with twelve rental car and car sharing companies (plus the three shuttle services who decide to jump in just because it doesn’t cost them much). I’d like to have the opportunity to see the responses, organized, in one place, with spam from the shuttle services filtered out. In fact, what I’d like is something like Kayak, which is a little like a Fourth Party in this context (I think.)

In fact, when I go to Kayak, I really am sending a very precise signal of intent, which each airline responds to based on its current pricing and availability. Nice #vrm.

It would be interesting to map more use cases. Again, I don’t think @DSearls wants to hear from fifteen grocery stores; he’d probably like a nice map that allows you to see available brands and sizes and prices at each location.

This is probably old news in the VRM community, but signaling intent without having an aggregator to “catch” the responses is probably asking for trouble. As a guy who bought a truck last year by asking for quotes from six Internet sales managers, and still hears from three of them now, “ask me how I know.”

David, that’s a great point. There certainly seems to be an opportunity for a Fourth Party to aggregate and manage intent in this way. That said,it’s the customer’s choice. For some things, managing the interactions directly might be preferred, for others, one might want to use an aggregator acting on one’s behalf. This mechanism would work in either case.

Chris,

Excellent deep dive on an important emerging topic, especially for the mobile-local-social consumer. Thanks for this post – I haven’t seen another one like it for a while.

We (NeedTagger) have thought long and hard about the pros and cons of using simple open text signals like this to signal personal intent. In short, we are huge fans of the idea.

That said, I believe there are at least two big stumbling blocks involved with an open public system that uses a simple text protocol to signal commercial intent, as follows:

1. An Open Invitation (and a Strong Incentive) to Spam: This type of “easy to detect” system is, by default, also easy to spam. If that happens, then we may end up creating personalized channels of spam that are similar to what you see today with self promoters stuffing hashtag channels.

Of course, in hashtag channels the “spam incentive” is getting a bad link/account retweeted. In a personal intent channel, though, the incentive is much greater – an order is at hand!

2. It’s easy for bad actors to “game” the system: a system like this can be used by unscrupulous competitors and third parties to send false signals into the intention economy – for example, to gather pricing & availability information they otherwise would not have available to them or to fool another organization or person into believing something false about true market demand.

I believe that many reputable brands & merchants will not participate (for long) if they see these types of shenanigans going on. After responding to tons of false signals and/or seeing their offers presented next to spam posts (with outrageously low prices, etc.), they may tire of the game.

However! if a trusted governing body or a major social network would adopt the protocol and monitor its (ab)use like crazy – with meaningful penalties for abuse – then we might have a shot at making a simple system work for all of us. And that would be a GREAT thing for brands, merchants, consumers and our economy overall.

Chris,

Brilliant. I love the simplicity of using a question mark for the “intent tag”.

The other commenters have already highlighted the key issue with this form of intentcasting: having to managing the reply channel.

It’s easy to say that a reputation system could supply the necessary incentives not to spam such a reply channel. But much harder to do.

In any case, that’s what we’re hard at work on with http://connect.me/ and http://respectnetwork.com/.

We can’t wait to get to Doc’s Intention Economy.

Quite an excellent idea. The only flaw I see is in the permission side, where a user might end up getting more attention from a seller than they might want. And, as other commenters have noted, it might be open to abuse/gaming/spam.

Thanks James. Totally agreed, and I think the mechanisms to handle a few bad actors are mostly in place. Twitter seems to do a (relatively) good job of getting rid of the bad actors on hashtags pretty quickly, overall. I would wager this would play out in a similar manner.